This story originally appeared in The Node, an online community created by the journal Development.

No parent wants to risk their child having a serious infection, least of all while still in the womb, but did you know that the immune response to a viral infection during pregnancy could also affect the development of the unborn offspring? Scientists from Harvard University in Cambridge, USA, have shown that immune reactions in pregnant mice are detected by a specific type of brain cell in the developing embryo and alter how genes are regulated in the brain – a change that persists in juvenile mice. Published today in the journal Development, this study provides new insights into how the maternal immune response might influence brain development in embryos and could help researchers understand the origins of neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism.

Scientists have long suspected that fetal exposure to infectious bugs may increase the risk of developing neurological conditions such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. There is also evidence that fighting infection while pregnant might affect the growth of offspring in the uterus, even if embryos do not become infected themselves. However, it has been unclear how embryos recognise their parent’s immune response and the exact consequences for their development.

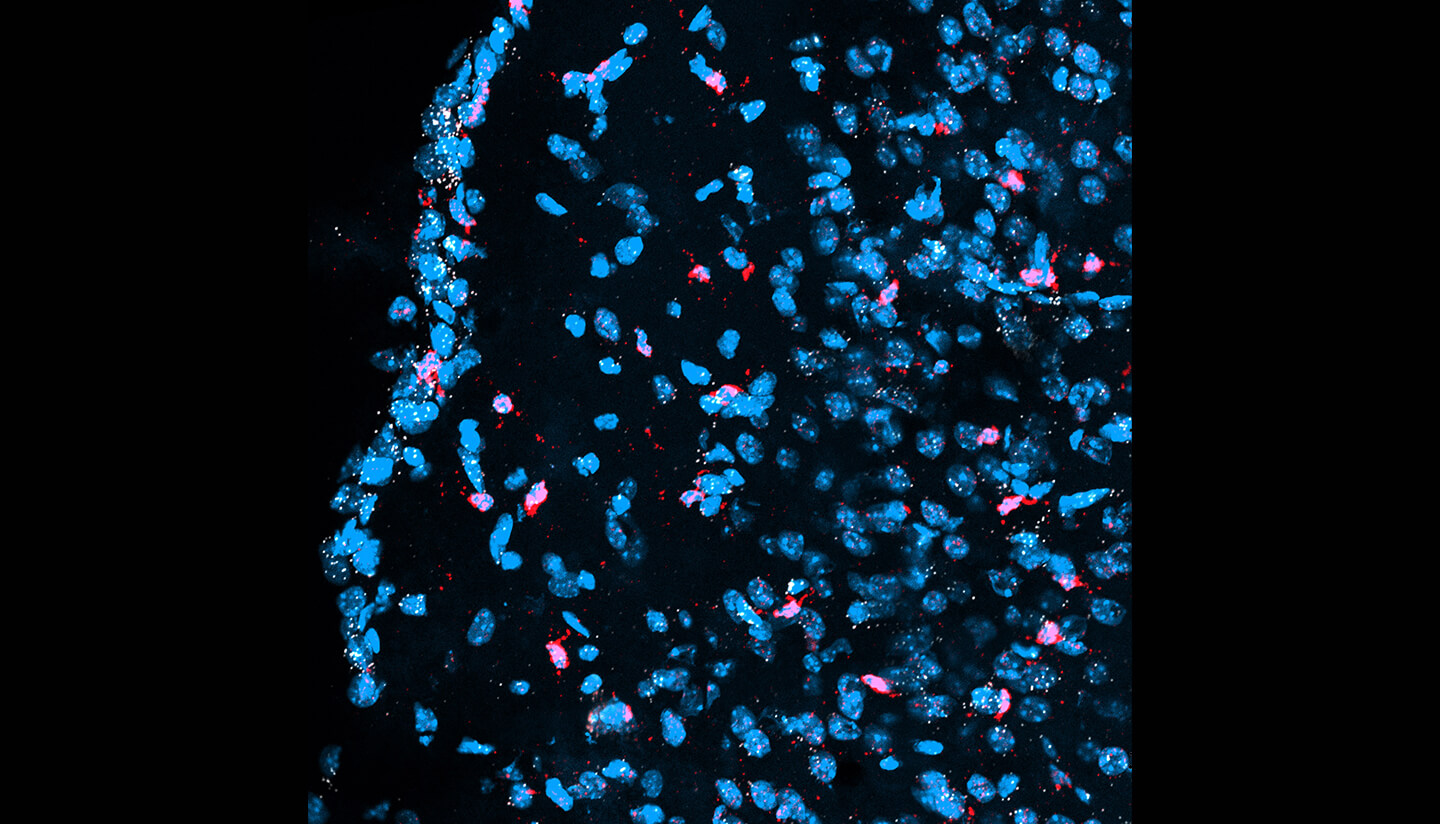

In their latest study, a group at Harvard University led by Professor Paola Arlotta have identified a specific cell type in the mouse embryonic brain that responds to an immune response in the mother. The researchers used a compound that mimics a virus to stimulate an immune response in pregnant mice without causing an actual infection. They then characterised how cells in the embryonic brain respond by assessing which genes were turned on or off. Using this approach, the scientists showed that cells called ‘microglia’ can sense the maternal immune response. “Microglia are the immune cells of the brain. They play a critical role during inflammation and infection and also have fundamental functions in healthy brain development,” explained Arlotta.

Following the mother’s immune response, embryonic microglia change which genes are activated or inactivated, which also occurs in the surrounding brain cells, such as neurons. Interestingly, the change of gene regulation in neighbouring cells depends on microglia being present in the brain; when the researchers repeated the experiments using mice without microglia, the other brain cells did not react to the maternal immune response.

Although most viral infections are often short-lived, the scientists found that the changes that the maternal immune system causes in embryonic brain cells persist well after the immune reaction has subsided. “Based on previous studies demonstrating that microglia exposed to early infections respond differently to stimuli in adulthood, we hypothesized that the maternal immune response could induce changes in microglial gene regulation that persist postnatally” said Dr. Bridget Ostrem, co-author of the study.

This research enhances our understanding of the cellular basis of neurodevelopmental disorders in humans. “Our results suggest a potential role for microglia as therapeutic targets in the setting of maternal infections,” said Ostrem, although there is still more work to be done. Harvard researcher Dr. Nuria Domínguez-Iturza added, “next, it will be crucial to determine the long-term behavioral implications of the changes we observed in this study.”